Over the last few years many services have appeared, that use the WiFi signals emitted by smartphones to monitor the presence of people. The leading application of such services has been in the retail analytics sector, where they are widely used to monitor how many people pass in front of a store, how many enter it, how long they stay, how often they come back etc.

Figure 1: Retail customer model (courtesy of

RetailerIN

)

Figure 1: Retail customer model (courtesy of

RetailerIN

)

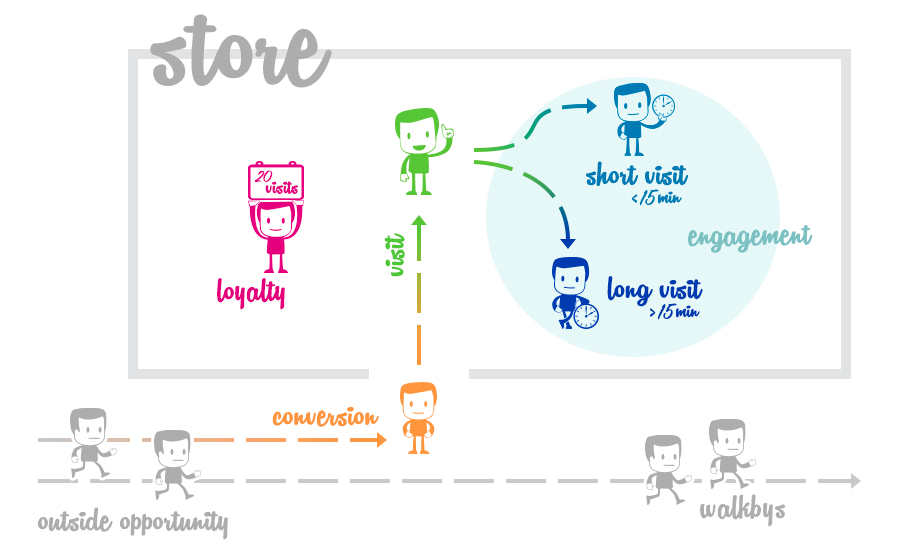

To better understand their use in retail we probably need a little step back. Traditionally, retailers have measured the number of people entering their store. First they used passive infrared technology, then moved to cameras (stereo, 3d, thermal.. you name it). Typically such cameras hang close to the entrance door and can tell how many people enter the store and how many people exit it. Yet, they can’t measure how long people stay. And they can’t measure how often people come back to the store. These metrics are highly relevant for retail stores, in that they act as proxies of engagement and loyalty, respectively. And engagement and loyalty correlate strongly with sales.

This is where WiFi kicks in. It is still kind of a secret (at least for laypeople), but if you have WiFi turned on (no, I didn’t say you are connected to a WiFi network, you are just walking to office with the phone in your pocket and the WiFi turned on) your presence can be tracked. There is indeed one part of the WiFi standard that allows WiFi-enabled devices to advertise their presence. Technically, this particular procedure is termed active scanning, and the messages used are called probe request frames. Think of it as your phone shouting “Hi, I am here!”. This was introduced in the standard to enable phones to connect faster to a known WiFi network (one you have connected to in the past and is in your list of favourite nets). If works like this (more or less):

The point is that when sending out hello messages your phone is signing them with a ‘name’ that uniquely identifies it (formally: the MAC address of the WiFi interface). Think of it as kind of your fiscal code or (if you are based in the US) your social security number. And as no encryption is used here, anybody can see it. Which means that anybody with a tracker device (no NSA-like devices: a standard laptop running a proper software, and there are plenty of options, can make it) can track your presence without you noticing it.

Depending on how paranoid you are, you may feel scared that somebody can actually track where you go etc. Which is probably happening right now, actually. Of course, more correctly somebody can track the presence of your phone, but nobody can know that it is your phone. Still, people can track the location where your phone happens to be. Bye bye privacy?

You may wonder whether this is legal. The reality is that it’s in a kind of grey area. In legal terms people should wonder whether the MAC address of a WiFi interface is “personally identifiable information”, which is the kind of data that falls under personal data regulation and privacy directives. Most companies that do WiFi tracking for a living state it is not:

Despite what companies claim, regulators have a different opinion, in both US and EU, and clearly hint that the MAC address is actually personal information:

Refraining from taking a position here (I am not a lawyer…), the point is that tracking WiFi is getting rather common. And it does raise legitimate privacy concerns.

To address privacy issues Apple, starting from v.8 of its iOS operating system, added a WiFi MAC randomization feature. iPhones, when sending out hello messages, are using a randomized version of their real MAC address . Think of it as a fake identity. So you can still see the presence of a device, but such device may change its identity at any time (even multiple times during a same day), so that tracking becomes ineffective.

And Android? Well, also Android has added support for WiFi MAC randomization, starting from v.6 , but this feature is not used consistently by all phone manufacturers (see here for a detail description of what various vendors have done).

The question is then: provided that now many (we measured ~50%) of devices use WiFi MAC randomization, what is the statistical significance of the analytics provided by WiFi tracking? In other words, are these services (RetailNext, WalkBase, Euclid or even ourselves at RetailerIN) lying?

Some of them actually claim they use techniques able to ‘defeat’ MAC randomization. While it is in principle possible to do it (see this great article on various techniques and workarounds) this is not feasible in practice (trust us, we tried!). It would be a bit long to explain you the various techniques and why they fail (I might actually do it in a separate, more technical, post) but the reality is that randomized MAC addresses cannot be derandomized. Good for privacy! But what about analytics?

Most companies in the arena actually end up using only real MAC addresses and, assuming that they represent a statistically significant sample, use such data as the basis for their analytics.

But** this is just wrong from a methodological standpoint**. Devices using real MAC addresses are often old devices, which adds a big bias on the population sampled (this is known in statistics as sampling bias). And raises serious doubts on the effectiveness of the metrics computed.

So, is everybody lying? Yes and no. I can’t speak for competitors, but what our fellows are doing at RetailerIN is to do some rather complex statistical processing in order to compute good estimates based on both real and random MAC addresses. This builds on a continuously calibrated mathematical model that is based on the popularity of various smartphones (and how such phones use randomization features) to avoid (or, better: minimise) sampling bias.

Does it work? Well, our tests with ground truth (based on cameras) suggest more than 85% accuracy. So yes, it works fairly well after all 🙂